Searching Waveforms

I recently read the book “Shop Class as Soulcraft.” I enjoyed the book, but one section struck me in particular. The author, who runs a motorcycle repair shop, relates a story of a customer who brought him an 83 Honda Magna V45 motorcycle that had been sitting in storage for years and wouldn’t start. After unsuccessfully trying to talk the owner out of it, he discovered and repaired the problem that was keeping the bike from starting. But he noticed the bike also had a small oil leak. On the one hand, he felt a responsibility to owner to get the bike–which wasn’t worth the money it would take to repair it in the first place–working with the smallest amount of billable labor as possible. But he also felt what he describes as a selfish need to fix it correctly. He laments that “this lust for thoroughness was at odds with the work of human concerns in which the bike is situated, where all that matters is that the bike works.” He finally succumbed and replaced the seal, a much larger job requiring disassembly of most of the engine, but out of guilt didn’t charge the owner for much of the labor. He comments:

One theologian writes that “curiosity’s desire is closed, limited by the object it wants to know considered in isolation: the knowledge curiosity seeks is wanted as though it were the only thing to be had.” The problem with such fixation is that the mechanic’s activity, properly understood, is practical in character, rather than curious or theoretical.

Having written software as a day job for a while, I’ve felt the tension he describes. I recently read a blog post where the author encouraged developers to “choose boring technology.” And, while that advice seems practical, it is deeply unsatisfying.

The beauty of hobby projects is that I feel little guilt for diversions. It’s in this spirit that I recently resurrected my waveform viewer project. A waveform viewer is an essential complement to open source hardware simulators like Icarus Verilog or Verilator. Before creating this project, I used GTKWave, but became dissatisfied with it. I don’t mean this as a slight on GTKWave, which is a great tool that has been useful to me. But tools built by other people never do exactly what you want.

My source code is here: https://github.com/jbush001/WaveView

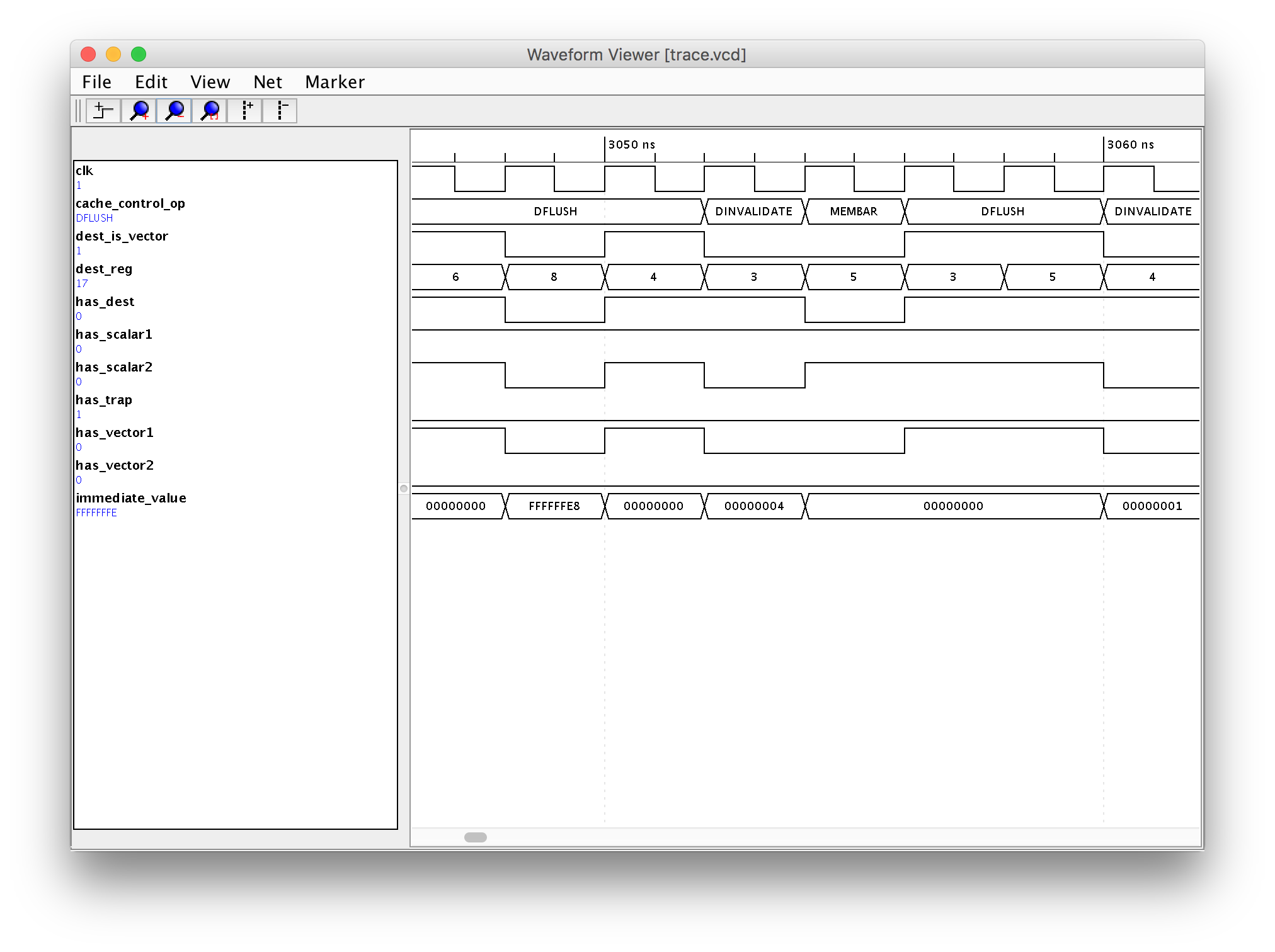

Here’s a screenshot:

One of the features I wanted in my app was a flexible and fast way of searching waveforms. For example, to find a place where signals values match:

a = 1 and (b = 2 or b = 3)

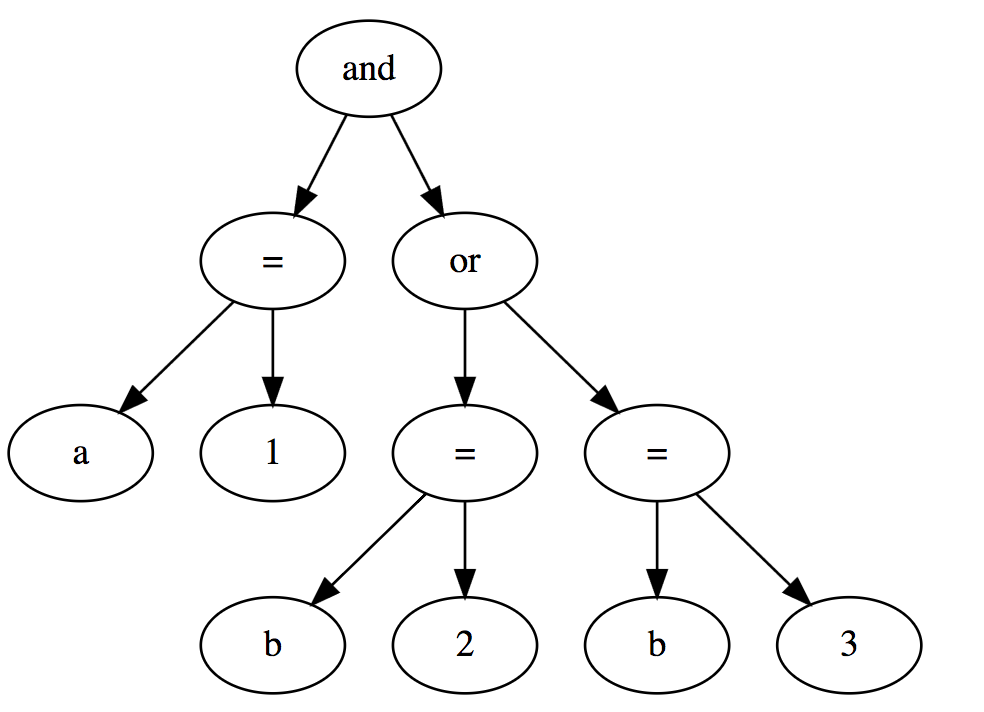

The code for this is in Search.java The first step is to parse the expression string and produce a tree data structure that represents it. For the expression above, it would look like this:

The program can test if the expression is true by recursively walking the tree, but it needs to evaluate it at a specific time. The time to search at is a parameter to the recursive evaluation function and the nodes that represent values (a and b) will perform a lookup to determine the value of their corresponding signal at the given time.

The app stores arrays of transitions, each which has a timestamp and the new value. Instead of allocating millions of objects to store this as an array of structures, I use two arrays: one for timestamps and one for values (I measured the former and it was both slower and used more memory). The fTimestamps array stores the absolute time of each transition. The fValues array stores the bit-packed values. Each net has its own timestamp and value arrays.

private long[] fTimestamps;

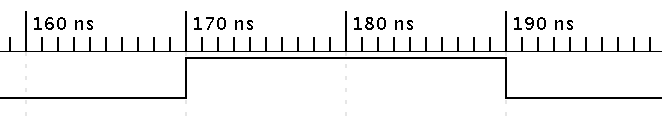

private int[] fValues;Since these values are time ordered, a binary search is an efficient way to find the value at a specific timestamp. But it is often the case that the timestamp it is looking for is between two transitions. For example, in this case, we may want to know the value at 180 ns, but there are only transitions at 170 ns and 190 ns.

To determine the value of the signal at 180 ns, it needs to find the first transition that occurred before that time, in this case at 170 ns.

Here is the code for the binary search:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

public Iterator<Transition> findTransition(long timestamp) {

int low = 0;

int high = fTransitionCount - 1;

while (low <= high) {

int mid = (low + high) >>> 1;

long midKey = fTimestamps[mid];

if (timestamp < midKey)

high = mid - 1;

else if (timestamp > midKey)

low = mid + 1;

else

return new TransitionVectorIterator(mid);

}

return new TransitionVectorIterator(low == 0 ? 0 : low - 1);

}

In the case where there isn’t an exact match, low will always be equal to the index of the transition after the requested key. I had to think about this a bit to understand why, but it comes down to this: whenever the key is between two timestamps, mid will always round down to the lower index, because it is an integer. For example, if low is at index 5 and high is index 6, (5 + 6) / 2 = 5.5, which rounds down to 5. Since the search key is greater than the timestamp at index 5, it will increment low to index 6.

When there isn’t an exact match, the loop exits and the return statement at the bottom of the function returns low - 1. The conditional returns 0 in the special case that the lookup value is before the first transition.

This binary search mechanism is also used when drawing the trace to skip events that are not visible.

Each time the app user clicks the find button, I want it to search for the ‘next’ place where the expression is true. If the condition is false at the current position, it will search forward until it becomes true. But if it is already true, what to do? Advancing forward by one nanosecond isn’t going to be useful. After some thought, I decided what I want to do is search forward until the expression becomes false, then search from there until it becomes true again: Imagine the case where a signal indicates a transfer is active. The transfer takes multiple cycles. Each time the user clicks the ‘next’ button, it jumps to the next place where a transfer begins.

To search, it needs to iterate through transitions, checking the expression value at each one. If this only supported searching one signal, this would be easy: it could increment the index into the transitions array to find the next one. Things become more interesting when searching multiple signals with a logical connectives like ‘and’ and ‘or’, since some signals change before others. The approach I’ve chosen is to have each node in the expression tree return a “hint” of the next timestamp that it should check. These hints start at the leaf nodes and propagate up the tree.

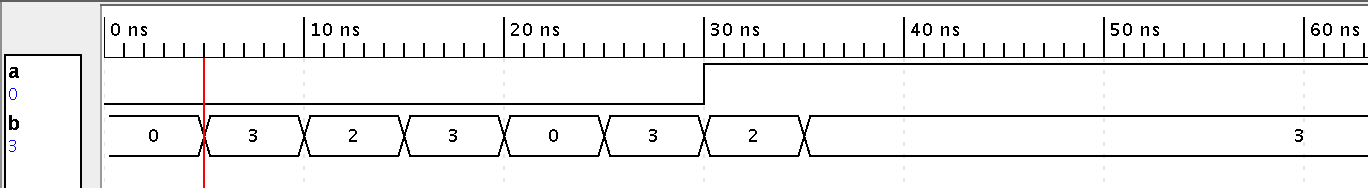

Here’s an example of a more complex waveform.

Assume I want to search for a place where the expression “a = 1 and b = 3” is true. The cursor is at 5 ns. Here is the raw data for this waveform.

“a” transitions:

| index | timestamp | value |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 30 | 1 |

“b” transitions:

| index | timestamp | value |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 5 | 3 |

| 2 | 10 | 2 |

| 3 | 15 | 3 |

| 4 | 20 | 0 |

| 5 | 25 | 3 |

| 6 | 30 | 2 |

| 7 | 35 | 3 |

At time 5, a is 0 and b is 3, so the condition is not true.

When it does the lookup for signal a at time 5, it finds that the most recent transition before that is index 0 at time 0. The next index 1 has a timestamp 30, so it returns this as the hint.

The lookup for b returns the value 3 (index 1, timestamp 5). The next event is index 2, which has the timestamp 10. It returns that as the hint. Note that b will not be equal to expression will not match at that index, but it doesn’t check that at this point.

There is an opportunity for an optimization. I know that it is impossible for the expression to be true at time 10 without even looking at the values at the next index. For the expression to be true, both a and b must match the values and both now do not. So, the next place where it could possibly match must be the earliest place where both signals have changed.

More formally, the AND node implements the following logic to compute its hint:

- If both children are currently false, the condition cannot become true until both of them change. This means it should take the latest (largest) of the two returned hint timestamps.

- If one child is true and the other false, the value can’t become true until at least the false child changes, so return the hint for the child that is currently false.

- If both children are currently true, the AND node could become false if either changes, so return the earliest (smallest) of the hint timestamps.

The OR node follows similar logic, but reversed. This scheme allows combining an arbitrary series of AND, OR, and comparison expressions.

Back to our example: by virtue of rule #1, the next timestamp it checks after 5 is 30 (largest 30 and 10). At that point, the comparison for node a is true, but b is still false. Using rule #2, the next hint for the AND expression would be the next transition for b, which is at time 35. At that point the expression is true.

The search loop looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

public long getNextMatch(long startTimestamp) {

SearchHint hint = new SearchHint();

long currentTime = startTimestamp;

boolean currentValue = fSearchExpression.evaluate(fTraceDataModel, currentTime, hint);

// If the start timestamp is already at a region that is true, scan

// first to find a place where the expression is false.

while (currentValue) {

if (hint.forwardTimestamp == Long.MAX_VALUE)

return -1; // End of trace

currentTime = hint.forwardTimestamp;

currentValue = fSearchExpression.evaluate(fTraceDataModel, currentTime, hint);

}

// Scan to find where the expression is true

while (!currentValue) {

if (hint.forwardTimestamp == Long.MAX_VALUE)

return -1; // End of trace

currentTime = hint.forwardTimestamp;

currentValue = fSearchExpression.evaluate(fTraceDataModel, currentTime, hint);

}

return currentTime;

}

The advantage of this approach is that the example above only needed to evaluate the search expression at two timestamps, rather than the six it would need to have if it had checked at every transition after the cursor. On the flip side, each time this checks a new timestamp, it must do a binary search on each signal referenced to find the value at the new time. For a, this is more work than simply stepping to the next transition index. For b it probably breaks even, but there are other cases where the binary search would be more efficient than stepping one index at a time.

It would be possible to use more sophisticated optimizations, like caching indices and avoiding a binary search in some cases. But these would harder to test, and it’s not clear that there would be a large performance win, so I leaned on the side of simplicity.