Waiting in Line...

I updated the simple 3d engine running on the GPGPU I’ve been hacking on to use a more sophisticated runtime. The original incarnation of the engine used a single strand to perform all of the work serially. That won’t scale up to multiple cores and performs suboptimally as utilizing hardware multi-threading is essential to get good performance on this architecture.

I scratched my head a bit on how to approach this. The basic concept is relatively simple, but I found a edge cases with all of the solutions I initially considered. I studied a few similar architectures while thinking about it:

- The original Larrabee paper described a system where functions are statically assigned to cores. Within each core, hardware threads are also given fixed functions based on the stage type. Each core typically renders an entire set of triangles on the front end or an entire tile on the back end.

- The GRAMPS project seems to build on the ideas of Larrabee, utilizing a more flexible model. It dynamically creates a graph of user defined stages, connected by queues.

- Cilk has a very powerful and flexible system for scheduling jobs. It is oriented towards heterogenous tasks and is doesn’t seem really appropriate for a graphics rendering pipeline, but I found a number of interesting insights and ideas from the documentation.

I decided to go with a relatively simple design to start. The four hardware strands pull jobs out of a single, shared work queue and execute them to completion. Each job may in turn enqueue jobs for downstream stages with the results of its processing. In this program, there are only a few types of jobs:

- A single job at the beginning transforms the vertices and batches them into triangles, creating a new job for each one.

- The rasterization stage computes the coverage of each triangle and creates jobs to fill the pixels. It does this by recursively subdividing the scene into 4x4 grids and creating many smaller jobs with coverage masks (more information about the general algorithm is available here).

- The fill stage write the pixel values into the framebuffer. This is where more complex pixel shading normally would be performed, but in this case the “shader” just selects a flat color value.

The pipeline looks like this:

The Verilog simulation renders this rather unimpressive looking cube:

As it turns out, the performance of this implementation is not great. It takes about 82,000 machine cycles to complete rendering the object into a 64x64 pixel framebuffer. However, understanding why it performs poorly is a useful start toward implementing something better.

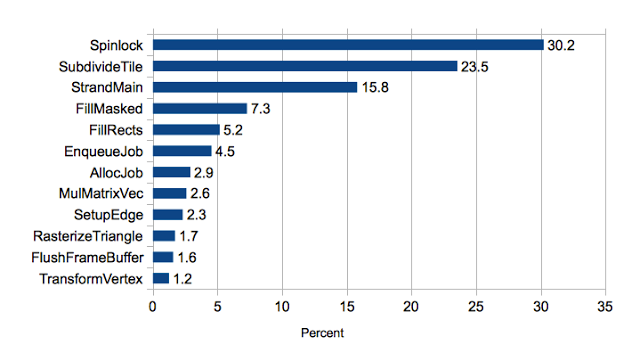

Synchronization Overhead

A big concern with any parallel design is the cost of locking and synchronization. I profiled the program by logging program counters of issued instructions and tabulating results (by function) with a script. The results aren’t unexpected, but I was a bit surprised just how much synchronization overhead there was:

Almost a third of the time is spent just acquiring the spinlock. If we add the other runtime functions (AllocJob, EnqueueJob, and StrandMain), over half the execution time is spent just in task management overhead.

Locking impacts performance in two ways:

- Contention is strands waiting to do work while other strands are in the critical section.

- Overhead is to the fixed cost of acquiring a lock–even in the non-contended case.

The degrees to which locking introduces these is generally affected by the granularity.

- Finer grained locking implies more locks and smaller critical sections. This generally reduces contention, but introduces more overhead.

- Coarser grained locking has fewer locks and does more work in each critical section, reducing overhead at the cost of contention.

The design of locking involves tradeoffs and it’s important to understand whether the locking is too fine grained or not fine grained enough. Using a script (firmware/3d-engine/analyze-contention.py), I can measure how many times a spinlock looped waiting to acquire the lock.

The results show that in only 24% of instances did a thread immediately acquire a spinlock. In the remaining 76% of cases, it needed to loop at least once waiting for the lock. Furthermore, the spinlock is acquired a total of 726 times in the simulation, but it ends up spinning a total of 3678 times. This means, if the lock were non-contended, it would take about 5x fewer instruction issue cycles. Since the spinlock routine is the most expensive routine in the program (taking 30% of the issue cycles), this is significant.

This suggests breaking this down into multiple queues would improve performance significantly. It also probably explains why other rendering architectures don’t typically use a single work queue.

I subsequently rewrote the entire engine in C++ using a binning approach, which removed most of the synchronization between threads. The new program utterly crushes this one in terms of performance. Using a queue for pixels turned out to be a horrible design.